JBL Kulübü Pro + TWS Kılıfı t220 karikatür köpekler / kediler Silikon kaymaz Kulaklık koruyucu kapak jbl ayar 220 / t 225 tws kılıfı < Taşınabilir Ses Ve Video ~ www.humaotomotiv.com.tr

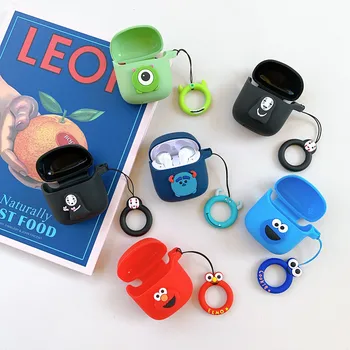

Cute Soft Silicone Cover for JBL TUNE 220TWS / T225TWS Case Bluetooth Earphone Case for TUNE 225TWS Case Earphone Headphone Box - Price history & Review | AliExpress Seller - Lsun 3C

JBL TUNE 220 TWS Kılıfı Için Sevimli Karikatür Silikon Kapak Bluetooth Kulaklık JBL T220 TWS Taşınabilir Zil Halkası Için Kılıf Yeni Joom Online | islamiyyat.com

JBL-Tune 220 TWS Kulaklık için Karikatür Figürü Koruyucu Kılıf Silikon Tam Kapak uygun fiyatlı satın alın - fiyat, ücretsiz teslimat, fotoğraflarla gerçek yorumlar - Joom

NOKOER JBL TUNE 220TWS için Cilicone Kılıf, Ultra ince yumuşak Kapak, İnce Kesim, Düşmeyi Önleyici, Kolay Kirlenmez, JBL TUNE 220TWS Kılıf, JBL TUNE 220TWS Kapak - Sarı : Amazon.com.tr: Elektronik

JBL Tune 220TWS Kulak İçi Bluetooth Kulaklık Siyah Fiyatları, Özellikleri ve Yorumları | En Ucuzu Akakçe

Sevimli karikatür silikon kapak JBL ayar 220 TWS / T225TWS kılıf Bluetooth kulaklık kutusu için ayar 225TWS kulaklık kulaklık kutusu _ - AliExpress Mobile

DIY Fruit Case for JBL TUNE 220TWS Case Bluetooth Earphone Case for JBL TUNE 225TWS Earphone Case bag with Finger Ring - AliExpress

JBL Kulübü Pro + TWS Kılıfı t220 karikatür köpekler / kediler Silikon kaymaz Kulaklık koruyucu kapak jbl ayar 220 / t 225 tws kılıfı < Taşınabilir Ses Ve Video ~ www.humaotomotiv.com.tr

JBL 220 Tws / Ayar 225 Kılıfı Karikatür anahtar kancası Silikon Koruyucu Kılıf JBL 220 kablosuz bluetooth Kulaklık Kapağı almak - Taşınabilir Ses Ve Video < www.ulusanmotor.com.tr

Tws Silikon Düz Renk Koruyucu Kılıf Bluetooth Kulaklık Koruyucu Kılıf Jbl Tune 220 Için | forum.iktva.sa

Tws Silikon Düz Renk Koruyucu Kılıf Bluetooth Kulaklık Koruyucu Kılıf Jbl Tune 220 Için | forum.iktva.sa

JBL TUNE 220 TWS Kılıfı için Sevimli Karikatür Silikon Kapak Bluetooth Kulaklık JBL T220 TWS Taşınabilir Zil Halkası Için Kılıf Yeni uygun fiyatlı satın alın - fiyat, ücretsiz teslimat, fotoğraflarla gerçek yorumlar - Joom

Diy Sevimli Yumuşak Kapak Için Jbl Ayar 220 Tws Kılıf Bluetooth Kulaklık Kılıf Için Jbl T220 Tws Kulaklık Taşınabilir Ile Parmak Yüzük Satılık! / Taşınabilir Ses Ve Video \ Simgeantalis.com.tr

Satın almak online Orijinal JBL T220TWS kablosuz kulaklıklar Bluetooth Gerçek Kablosuz Kulaklık HARMAN Stereo Müzik mikrofonlu kulaklık, şarj Kılıf \ diğer > www.alesclub.com.tr

JBL Tune 225 TWS/220TWS için Silikon Kılıf Kaybolmaya Karşı Darbeye Dayanıklı Koruyucu Kılıf Kapak JBL Tune 225 TWS/220TWS ile Uyumlu (Sarı) : Amazon.com.tr: Elektronik

NOKOER JBL TUNE 220TWS için Cilicone Kılıf, Ultra ince yumuşak Kapak, İnce Kesim, Düşmeyi Önleyici, Kolay Kirlenmez, JBL TUNE 220TWS Kılıf, JBL TUNE 220TWS Kapak - Sarı : Amazon.com.tr: Elektronik